Why Canada’s athletes are struggling financially

![]()

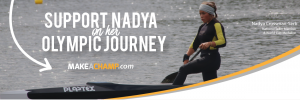

Help Winnipeg paddler Nadya Crossman-Serb on her Olympic journey!

Click here to read more about Nadya, or visit her MAKEACHAMP page.

Why Canada’s athletes are struggling financially

Athletes are better, faster and stronger today than ever before. Advances in sport science, sport medicine, nutrition, and strength and conditioning in the last two decades have allowed elite athletes to do the impossible. In Canada, 2016 showed a successful Games as athletes came home with their largest ever medal haul at a Summer Olympics.

And yet, many of them are unable to make ends meet.

Rio 2016

The Rio 2016 Olympic and Paralympic Games were a glorious month for sports fans in Canada.

Penny Oleksiak became Canada’s most decorated athlete in one Olympic Games at the age of 16. 21-year-old Andre De Grasse challenged Olympic legend Usain Bolt on the track in breathtaking fashion, and Canadian flag-bearer Rosie MacLennan defended her Olympic title.

At the Paralympic Games, 20-year old swimmer Aurélie Rivard won four medals herself in the pool, including three gold. Michelle Stilwell raced her way to two gold medals on the track while Canada’s track cycling team made podium moments look routine with their medal haul in Rio.

As the lights dimmed and the celebrations came to an end, Canada’s elite athletes returned to a darker reality.

The cost of being elite

Every year, Sport Canada directly funds aspiring and current Olympic and Paralympic athletes through the Athlete Assistance Program (AAP). Their annual budget includes $28 million in AAP carding money to high performance athletes.

This money is distributed amongst approximately 1,900 of Canada’s top high performance athletes across more than 80 different sport disciplines. This averages out to about $1200 per athlete per month; specifically $1500 a month for Senior carded athletes, and $900 a month for Development carded athletes.

While additional support for able-bodied and parasport athletes is provided by the federal government through more than 50 National Sport Organizations, many high performance athletes in Canada are failing to stay in the black.

In part, this is due to increased costs in sport, such as travel, equipment, and sport science costs. In the next fiscal year, the Government of Canada may increase its AAP carding budget. Doing so would be the first AAP carding increase since 2004. In the time since then, inflation has increased living costs and daily expenses by 25%.

To athletes, this is the equivalent of losing a quarter of their annual salary in little over a decade.

The numbers

A 2014 report from Sport Canada showed that carded athletes had an average annual income of $25,616. In contrast, their expenses on average amount to nearly $40,000 a year.

Just under half of those expenditures are sport-related, while slightly over half are necessary living expenses such as housing, food, and hydro.

$1,200 per month – average AAP carding money

$2,052 per month – average living costs

$1,460 per month – average sport-related costs

The average carded athlete in Canada faces a deficit of nearly $15,000 a year. For athletes aged 20 years or younger, this number is closer to $30,000 a year.

While training costs and income can vary widely amongst Canadian athletes, those hurting the most are individual sport athletes living and training outside their home province. Individual sport athletes spend over twice as much as team sport athletes do on their sport-related costs.

Non-government funding is distributed mostly to National Sport Organizations (NSOs) with a history of success, meaning athletes in non-targeted sports are suffering greatly. Several smaller NSOs are unable to fund their athletes even at large international competitions and World Championship events.

What it means

As the world’s best athletes try to focus on performing on demand, financial woes remain a very real performance barrier. Training, now more than ever, is a full-time job. Physical, mental, and emotional demands on elite athletes are the highest they’ve ever been.

Training camps, competitions, travelling, and other obligations throw a wrench in part-time income prospects, and locking down sponsorship is exceptionally difficult for anyone who hasn’t stood on an Olympic or Paralympic podium. Ultimately, many athletes afford to train, compete, and fulfil their Olympic and Paralympic dreams on the dollar of their friends and family.

Canadians are ending their careers well before they peak – committing to a second or third Olympic or Paralympic quadrennial doesn’t just mean another four years of incurring debt, it means another four years of forgoing full-time education, employment and professional advancement.

Away from an Olympic and Paralympic stage, following the high performance path is far from glamorous. It requires continuous grit and determination from the athlete, and the support of the community around them. It is a resource-intensive commitment that is not evident to the public eye in the few minutes of broadcasted competition.

From an outsider’s perspective, Canadian athletes look to be thriving, and in a sense they are. Olympic and Paralympic medal counts are higher than ever, Canadian records are being crushed, and for that bright Olympic and Paralympic Games window every two years, all seems to be well, the challenge is making it there.

Behind the glory of it all, the pursuit of excellence is a costly choice.

Clarification:

This is a corrected story. Figures and wording in “The cost of being elite” and “Rio 2016” sections were updated on Wednesday, March 22, 2017 at 10:54 am.

In addition to AAP carding money, the Government of Canada, through Sport Canada, contributes a portion of the $146M through the Sport Support Program budget to high performance sport, including $17M annually to all seven members of the COPSIN network and $60M toward targeted sports and athletes through recommendations from Own The Podium.

Nadya Crossman-Serb is one of Canada’s best female canoeists.

The Winnipegger has been paddling since she was eight, and has always dreamed of competing at an Olympic Games.

At 20, Nadya has already won multiple national titles, silver at the 2016 U23 World Championships, and gold at her first ever senior World Cup.

Nadya has quickly become dominant on both a national and international stage and is on the road to compete at the Tokyo Olympic Games. The 2020 Summer Games will include women’s canoeing in its program for the first time.

To continue along her path to Tokyo, Nadya must raise $7,000 before May 2017 to pay last year’s costs for her international competitions. Her participation in National Trials and all international competitions this season depends on whether or not she can secure this funding.

Read more about Nadya or click here to support her today.